Black History and the Fight for Fair Housing

By Brittany Holmes, Public Advocates and Alliance for Housing Justice

When we learn and talk about history, especially Black history, we don’t often connect those past actions to the impacts of today. Not only do the actions of the past affect the present, but many of the problems of the past have not been eradicated.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is talked about as a leader of an era that fought against racism, which is true; however, the other narrative pushed with his legacy is more subtle—that the problems that plagued people of color disappeared when he was murdered, and the country was overcome with understanding and racism disappeared. This could not be further from the truth, as white supremacy and its long history are still alive and well (and even those attempting to undo MLK’s work quote him). Even though his assassination compelled some people to move forward, the systemic problems that exist have not disappeared and should be focused on all year and not just during Black history month. The problems that MLK faced up until the 1960s still exist today. In fact, MLK’s fight for fair housing is under attack just as much now as it was then.

Today, people of color still face discrimination in housing. For example:

- The difference between loan approvals for Black and White ownership is worse now than 100 years ago.

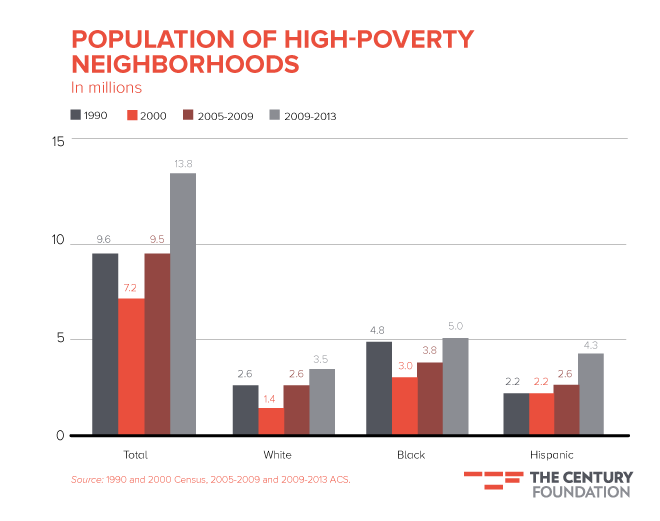

- Across the country, exclusionary zoning, or snob zoning, prevent affordable housing from being built in certain areas that maintain segregation of different income families, which allowed all white communities to exist and continues to raise the rate of concentrated poverty.

- Concentrated poverty also impacts low-income families by typically having a lower quality of public goods since there are fewer property taxes collected in the area. This means lower quality schools, roads, parks, among less access.

Do housing laws exist to protect people from discrimination?

Yes! Unfortunately, they are not vigorously enforced. After so many years, there are many court rulings and policies that have been heard, but few have been enforced to their full extent. Laws such as Disparate Impact are not enough to change history alone.

If the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) rule that came from the Fair Housing Act of 1968 had been implemented in its entirety, we could have seen great progress in dismantling the historic, systemically racist housing practices. This is one of the policies that we could fight for to be fully implemented and enforced. Yet, communities and people of color are still fighting the same battles as MLK did over 50 years ago.

Even more importantly, if these laws were implemented to their fullest extent today, they could not undo the massive, debilitating history of discriminatory housing practices without the support of citizens demanding better. The stories of people getting turned down for housing opportunities because of their skin color are numerous, and even tangle with the history of the current president. Because of this unfair treatment of people of color, especially with homeownership, amassed wealth has been lost for generations and those that did purchase homes were given predatory lending rates.

What unethical practices got us to where we are today and how does it impact us?

There are many reasons why we are here today, but here are just a few.

Land Grant Institutions

One piece of legislation signed by Abraham Lincoln created had a profound effect on higher education, especially when it enabled discrimination. In 1862 the Morrill Act was passed, allowing for 30,000 acres of land to be given (taken from Native communities) to each state in order to create colleges that taught practical professions during that time. This revolutionary commitment to higher education is still praised by many, but it is often forgotten that Black students and farmers were not able to attend these new colleges, and a second Morrill Act in 1890 allowed for land to be used for Historically Black Colleges and Universities.

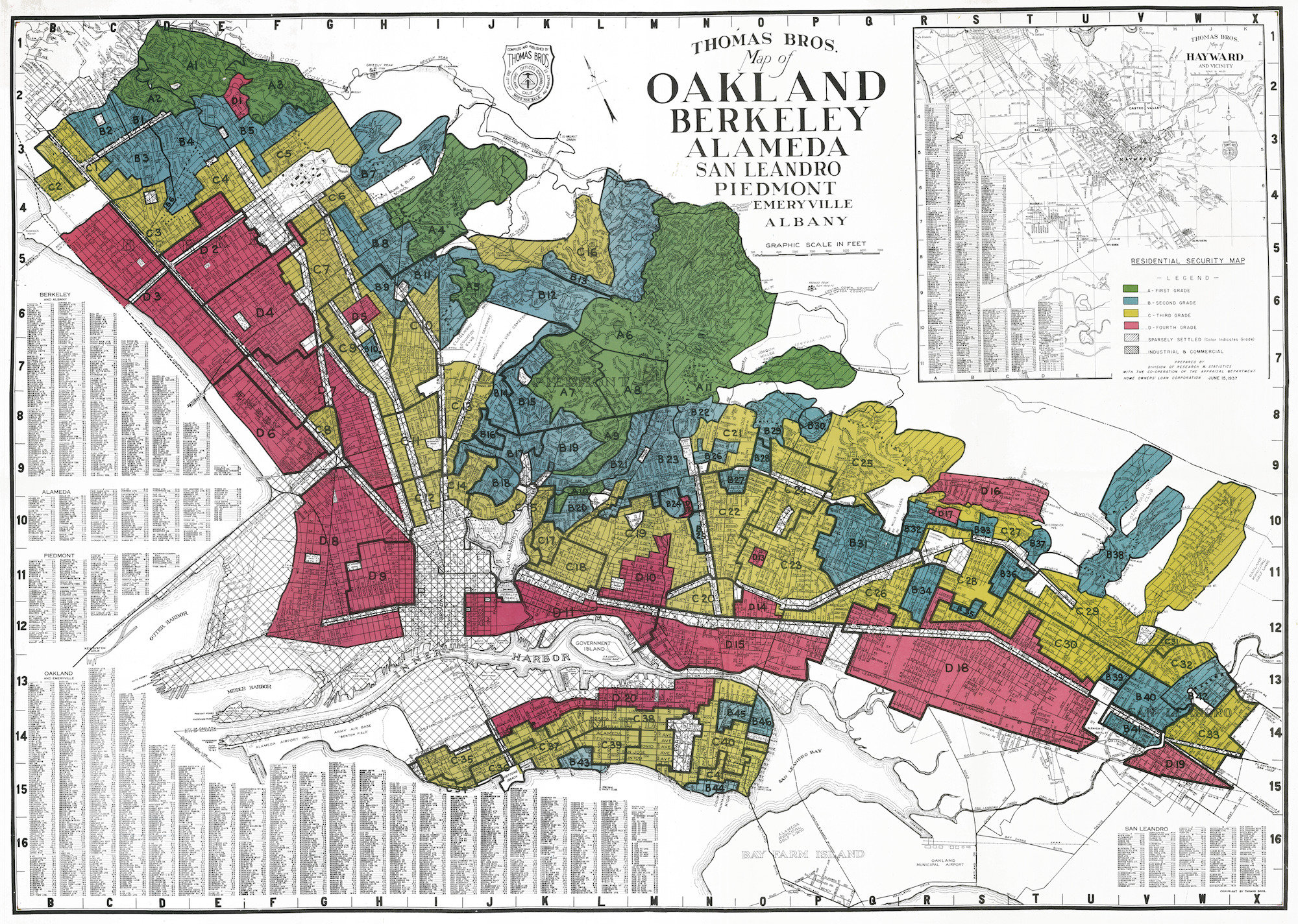

Redlining/FHA Lending/Restrictive Covenants:

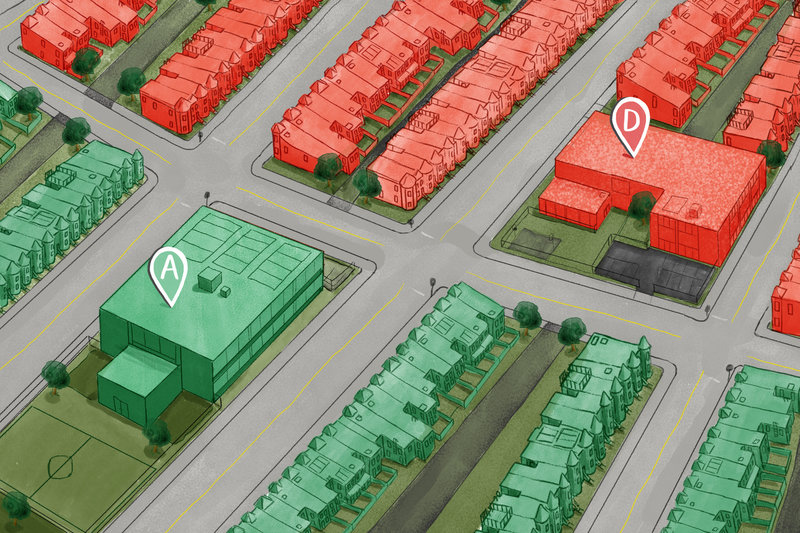

In order to decide “good” investments, banks and loan companies kept maps of cities to show them where the most valuable areas were. Yet the people that made those maps believed that people of color affected neighborhood desirability, and then rated the neighborhoods with more people of color as “D” or the worst investment area possible for mortgage lenders, and colored it red. What is worst, is that this was a policy created by the Federal Housing Administration in 1934. This is redlining. Its practice went on for a long time and the impacts can still be seen in maps today.

Racism was not only systematically embedded in the housing system by the government through redlining, but it was also written into the individual property restrictions using restrictive covenants. Starting in the 1920s, the language of deeds often stated that some properties were only allowed to be sold to white people, and even though it is not legal to enforce, some people still try.

How does the history of housing discrimination effect us today?

The impacts of discrimination and racist practices are seen throughout lives. It impacts:

Generational Wealth:

Since good and bad neighborhoods were defined, and only certain people were able to buy in specific neighborhoods, this allowed generational wealth amassed by real estate to be exclusive to white people. For example:

If a white family buys a home in a neighborhood rated “A,” and tries to sell it twenty years later, the banks still see that the family home is in an “A” neighborhood, and when they go to resell they know that the banks will still see their home as a “safe” investment for the next family looking to buy. Therefore the bank will grant another family a loan for the increased value of the home.

Now, if a Black family buys a home in a “D” neighborhood, it is shown that those houses do not appreciate much in value compared to the white counterparts. So, the Black family does not get as much money for their home as the white family.

If you compound that effect over generations, that is a lot of lost wealth by families of color.

School Quality:

The quality of nearby schools also plays a huge role in housing. Imagine you are between two homes, both equally appealing, but one has a better-rated school system. You likely would choose the better-rated school system. Even when touring a home without kids, a real estate agent will boast about a home being located in a great school district. This is added value to the home, which is another bonus as a home buyer. The cycle is vicious because, “in most places around the country, school budgets are partly linked to local property taxes. Highly rated schools beget higher housing values, which in turn beget more richly resourced schools.”

But let’s talk about those people without kids. Younger, wealthier people can come into a market and the area begins to gentrify, and the families that formerly filled that neighborhood have moved or been forced to leave. The schools can end up under-enrolled and end up closing, hurting the community members that have been there the longest.

In fact, schools are still segregated now—even more so than ever before.

Health Outcomes:

Redlining also impacts health to this day. Neighborhoods that were given a good rating have fewer infant deaths and highest life expectancies. More so, poorer communities have less access to healthcare and less stable living situations which impact the quality of life.

The effects of these racist conditions not only still exist, but undoing their impact takes more than upholding the laws that exist. It takes an active, thorough implementation of the laws and rules that exist.

How do we fix this?

We can not repair the suffering of those that have experienced such racism, but we can work to make sure that these systemically racist systems are no longer allowed to thrive and begin to work toward reparations. We do have rules like disparate impact and the tools like Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH), and we need to continue to fight for their power.

There are plans from the current Trump administration to roll back civil rights protections that fall under disparate impact. There is already fierce opposition for getting rid of these equalizing tools, but in the months ahead we are likely to see more push from the Trump administration and Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson to remove or fatally weaken both Disparate Impact and AFFH.

These racist practices should have never happened, and the roots of racism need to be dismantled. They have harmed too many and actively need to be undone and fought.

When we reflect on Black History Month, we need to remember that the fights for equality and equity are not a thing of the past. They are ongoing and have never stopped. Grassroots organizations across the country continue to fight for more equitable housing that dismantles the practice of white supremacy in the housing market and more resistance is needed. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said, “in the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends.” History is still being written. Will you be a part of it?

CarsonWatch is an organization that works to amplify the voices of those impacted by the housing crisis, educate the public on housing justice, and monitor the actions of HUD to uphold and enforce housing equality.

Join us in the upcoming fight against Trump and Carson.